When someone is being uncommunicative, lacking in common courtesies, sending curt emails, never smiling, permanently scowling, we can do without that, right? When we feel we are on the receiving end of this sort of unhelpful behaviour, how many of us actually mention how we feel to the person who may have ‘offended’ us? Things can fester over time until something small triggers matters, and then a grievance or bullying claim can feel like a good option. When work reaches the level of ‘overwhelm’, our reserves of listening, understanding and empathy can be stretched to the limit, particularly so when we perceive someone is treating us ‘badly’.

In my 27 years as an HR Director, I can’t say I have met many people who turned up to work determined to deliberately hack off their colleagues. There’s usually something amiss. Why is it we can often close our minds to finding out a bit more behind what’s going on, before deciding someone is ‘difficult’? If we remain curious, we might find out why ‘that person’ is being such a so-and-so. What have we got to lose? We can only gain.

What about those whose inexplicable behaviour might not always be a temporary blip. We now know a little bit more about the infinite array of neurodiversity – those who think differently – https://www.cipd.co.uk/Images/neurodiversity-at-work_2018_tcm18-37852.pdf. Nick Walker, author, speaker and educator tells us that a neurodiverse brain is one ‘that functions in ways that diverge significantly from the dominant societal standards of “normal”. He goes on to say that because of potential challenges with eye contact, tone of voice, shyness and social anxiety, some people with neurodiversity may appear to colleagues as aloof or unfriendly. This can be potentially exacerbated when empathy and understanding in the workplace is in short supply where employers are yet to embrace neurodiversity at work.

Mary (not her real name), a coaching client of mine, is a lawyer. She has a diagnosis of Autistic Spectrum Disorder; a condition related to brain development that affects how a person perceives and socializes with others. This can cause problems in social interaction and communication (https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/autism-spectrum-disorder/symptoms-causes/syc-20352928). Here’s Mary’s own honest reflection on what she feels it may be like to work with her.

‘I scowl. A lot. And, if I hear a tape recording of myself, even I am shocked at my monotone voice and how bored and condescending I sound. That’s not all. I also have a tendency to roll my eyes and wear an expression of contempt.

So, I can be highly offensive to work colleagues (well to everyone really). I have lost quite a few jobs over “my attitude.” If anyone calls me out on my behaviour, I’m baffled because I’m really not thinking what my face suggests I am. Then if, someone forces the issue, I become defensive and will probably start criticising them in return. It’s a hopeless muddle.

It gets worse. I am no better at reading other people’s expressions than they are mine. So, more offence, more misunderstanding because I am “insensitive.” If there’s too much going on, I get overwhelmed and shut down. I’m anxious and probably defensive, again.

The pandemic cuts the awkwardness. I keep the camera off on zoom meetings. No one has to look at me frown as I concentrate on what’s being said. Likewise, wearing a mask is great – I am starting to think I might keep going with the mask.

I work for a charity and my colleagues are awesome. They know that I am autistic. I think they’ve accepted I’m from a different planet – one where the language of facial expression, tone, and mannerisms is just alien and that I’m over sensitive, not insensitive.

The downside to lock down is missing out on social interaction. I camouflage my social difficulties by copying. My colleagues teach me to smile. Now we are all working from home, I don’t have anyone to copy anymore. I’m scared I’ll get things wrong when we’re finally together again – but I trust them to be patient’.

Through the coaching, Mary is making personal changes herself to help her better engage and communicate with others at work.

Not everyone demonstrating challenging behaviour at work is neuro-atypical but the same principles apply when any work relationship is showing strain and stress. My research, carried out this year under the auspices of the University of East London, found that if we could share (in a kind way), how we were feeling when things felt amiss; if we could ask someone ‘are you ok?’ before closing our minds about someone’s behaviour, it would help us gain a greater understanding of what’s going on.

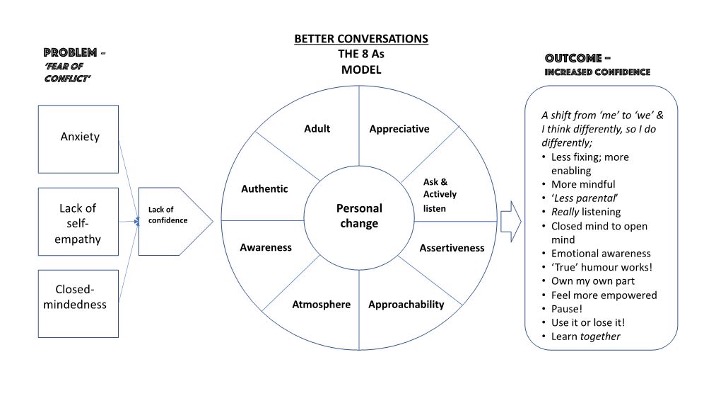

People can unwittingly contribute to their own lack of confidence, through fixed thought patterns and low curiosity to discover what lies behind the conflict before communicating. The TalkTrue 8As model© helped people positively reframe and make positive personal changes including deeper listening, greater self-empowerment, emotional regulation and more mindfulness. This resulted in increasing people’s confidence to engage in difficult conversations with each other. This accords with a growing number of studies applying positive psychology to addressing workplace stress e.g. Neff and Germer (2013).

Recent Comments